Maine Sunday Telegram, May 1998

Irish Painter Brings Exotic Places To Life with Rare Style

By Ken Greenleaf

Ray Farrell, proprietor of the O’Farrell Gallery, is drawn ever more insistently to Ireland, his ancestral home. He owns a home there, which he visits at every possible opportunity, returning with photos and dreamy tales of a distant land. Now he has brought a show of the work of an Irish painter, Vincent Crotty. Crotty is a young artist who now lives in the United States but was brought up in in the trade of sign painting in Ireland.

Trade schools are different there, as anyone knows who has hired one of their graduates. Crotty knows an awful lot about paint. The love affair with the seductive stuff of painting, with its blobs and strokes and layers and all the rest, has endured throughout the changes that have been progressively wrought in our understanding of what art is about ever since the days of the impressionists.

It is a taste required easily, and as part of the paintings content it has served everyone from Claude Monet to Hans Hofmann to Lucien Freud. The hard analysis of American modernism and the condescending irony of pop and post-modernism have minimized the alluring nature of paint itself as part of the whole deal in painting, but it remains induringly popular. Looking at Crotty’s paintings is a foray into at least two rather exotic worlds, the landscape of Ireland and a type of painting rarely seen these days. No mistake at all, things are a little different in his work.

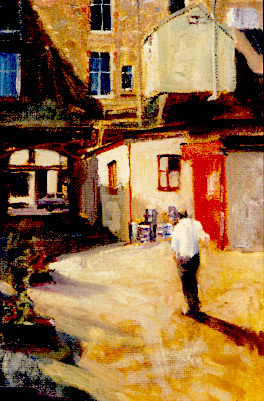

The barns and farmyard in “Hillside Farm” have a different architecture and are revealed by a light that is different from that which we see in paintings, and on the land, here in Maine. They are also painted with a style that is rarely seen among comtemporary artists. It is a meaty and efficient process in which a single streak of white paint serves duty as a whole section of the eaves of a barn.

Crotty has the ability to put together areas of paint that appear to have more detail than they actually possess. It is an illusion brought on by the way we can do simple, local modulations within the stroke itself so that the eyes see what it expects to see. The side of a sheep in the distance might be nothing more than a little irregular rectangle, but it convinces the viewer that this is, indeed, a careful rendering of a sheep.

The stooped figure in a scalley cap walking along a rain-soaked dirt road past a sheep pasture is not one that would be seen in Maine anymore. There is, in these paintings, an atmosphere of enduring values, or at least of values that nostalgia would lead us to believe ought to endure.

In terms of art techique, this is not exactly news. What is news is that it is a process that isn’t seen all the time nowadays. Coupled with, for the most part, subject matter that isn’t America, the show is appealling and enjoyable. The stooped figure in a scalley cap walking along a rain-soaked dirt road past a sheep pasture is not one that would be seen in Maine anymore. There is, in these paintings, an atmosphere of enduring values, or at least of values that nostalgia would lead us to believe ought to endure.

The distinction between Crotty’s artistic strategy and that of other loose, open-air landscape painters like, say, Chris Huntington, is instructive. Crotty’s depictions of life and light and landscape have detached, classical quality about them, as if the most important thing about the enterprise was the creation of a painting whose chief virtue is as an artifact of skill and observation. Crotty tells us how he can paint what he has chosen, and makes his choices according to the story he wants to tell. His subject is the barn, the walker on the road, the hills in the distance. The painting is a fiction about his subject that has been filtered through his skills as painter. An American antecedent might be John Sloan. Huntington, another painter with meaty technique, tells us about his own reaction to the situation he finds himself in. The action of the blobs of paint is not so much a means of getting a rendering completed as it is a record of his emotional life at the moment. Huntington’s subject is Huntington. The antecedents here are Albert Pinkham Ryder, Carl Sprinchorn and, of course, Hartley.

The almost objective detachment that Crotty brings to his work makes his paintings a breath of fresh air in the Maine artistic atmosphere. The show reminds us that there are other ways and places to paint, and other subjects besides the one we find in the mirror.