traditional signage

Traditional signage is an art form that has been handed down for centuries. In the old days, a train car would require 12 coats of paint, with each coat carefully applied by hand. Before trains, sign makers painted carriages, taverns, butcher shops, and coats of arms. In France, there are existing storefronts that were done in the 17th century, with reverse glass painting, wood-graining and carving, all sorts of old-world craft and design.

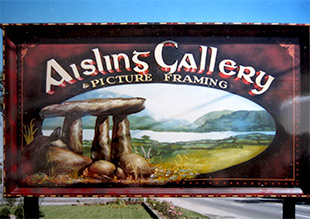

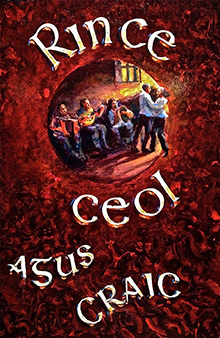

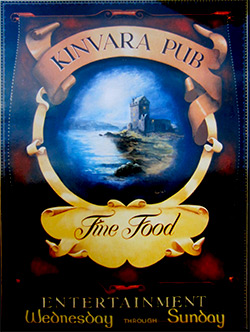

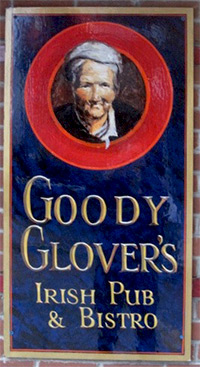

I make hand-painted signs that include techniques like wood-graining, marbleizing, freehand lettering, and pictorial designs. As a visual artist, I incorporate paintings (landscapes, still life, birds and wildflowers) as well as Celtic knot-work into my signs.

I was born in Ireland, and I learned the art of sign craft there, in my 20s. I trained in Cork City in a trade school called Fás, starting in 1987. My teachers Gerry Fitzgibbon and Noel McKenna gave me everything they had to offer, which was handed down to them through the traditional master-to-apprentice guild system. At the beginning of my training I was taught how to draw the letter O. I was working on old wallpaper — the back of it was rolled out in 20 foot strips — and I had to draw the letter O for the first week, over and over. I had to draw Os in 2 inches, 3 inches, and 4 inches, and by the end of that, I had a new-found confidence in to how to use the pencil. Then they graduated me into drawing the letter S and the letter B, and after that, I was free as the wind!

Before Fás, I had been inspired by the work of Tomás Tuipéir, a master sign painter from West Cork. He was a passionate artist and a generous mentor to me. I had many opportunities to visit him and watch him work.

When making a sign, I often start with the background first, preparing a board in broken color, meaning one color semi-transparently applied over another to create different effects. It’s a tradition that goes way back in history, but it was brought to a high art form in France and Germany in the 1600s. It was a way to mimic exotic wood or marble without having to use the real thing, because it was enormously expensive to bring in mahogany from Indonesia, or lapis lazuli from Afghanistan.

Then I draw the lettering in pencil, on tracing paper. After that, I put chalk on the back of the paper and transfer it to the prepared board. Then I use sign quills, which are special brushes (the tip of a feather shrunken around sable hairs), to do the painting and lettering. I was trained to do Roman lettering, script lettering, Old English, Celtic, and more. Once you’ve learned those letters, then when you are confronted with another alphabet, you have the skills to proceed. You’ve learned how to draw circles, triangles, squares, receding seriph shapes, calligraphic shapes (varying thin and thick lines, depending on the pressure of the brush), and so on. There is no machinery used in any of this, except saws to cut the sign board. Other materials I use include sign enamels, gold leaf, varnish, and shellac.

I worked as a traditional sign painter in my hometown of Kanturk, and then I came to the US in 1990, and continued my work here. Sign painting has been a wonderful trade to have, to supplement my living as a visual artist. I have created signs and decorative graphic work for restaurants, churches, pubs, the Irish Cultural Centre of New England, The Boston Irish Reporter, and other organizations. I’ve done storefronts and signage in Dorchester, Brookline, Hingham, Haverhill, Allston, Brighton, South Boston, the North End, and Government Center. I’ve done Indian restaurants from Roslindale to Dorchester to Huntington Avenue. I’ve tried to bring color harmony to each premise, and I’ve tried to make storefronts that reflect the community.

Church work is wonderful — you’re working on beautiful buildings that were built over 100 years ago. I’ve worked on St. Mark’s, St. Ambrose, St. Margaret’s, St. Peter’s, and St. Ann’s (all in Dorchester), and St. Ann’s in Quincy. I also worked on a synagogue in Brookline. When you work on these jobs, you can see the craftsmanship of people who lived a century ago — sometimes you have to repair that work and learn how it was done, so you can replicate it. In St. Mark’s Church, there is an alter that was hand-carved over 100 years ago, by a man from Florence. I actually met his granddaughter in the church. When you work in churches, you’re connected to all these things.

Traditional signage has been almost obliterated by the computer. A handmade sign has warmth and the human touch – it’s the opposite to the coolness of technology. There can be flaws in something handmade. If you do two Os beside each other — let’s say you’re writing the word WOOD — one O will have a slight difference to the next O. It’s not perfect, but it beautifies a place, and brings personality to the street. It’s a practical marriage between art and craft. There was a saying in my school in Cork: “The laborer works with his hands. The craftsman works with his head. And the artist works with his hands and his head and his heart.” I was greatly moved by that saying.